READING PASSAGE 1

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 1-13 which are based on Reading Passage 1 below.

The Dead Sea Scrolls

In late 1946 or early 1947, three Bedouin teenagers were tending their goats and sheep near the ancient settlement of Qumran, located on the northwest shore of the Dead Sea in what is now known as the West Bank. One of these young shepherds tossed a rock into an opening on the side of a cliff and was surprised to hear a shattering sound. He and his companions later entered the cave and stumbled across a collection of large clay jars, seven of which contained scrolls with writing on them. The teenagers took the seven scrolls to a nearby town where they were sold for a small sum to a local antiquities dealer. Word of the find spread, and Bedouins and archaeologists eventually unearthed tens of thousands of additional scroll fragments from 10 nearby caves; together they make up between 800 and 900 manuscripts. It soon became clear that this was one of the greatest archaeological discoveries ever made.

The origin of the Dead Sea Scrolls, which were written around 2,000 years ago between 150 BCE and 70 CE, is still the subject of scholarly debate even today. According to the prevailing theory, they are the work of a population that inhabited the area until Roman troops destroyed the settlement around 70 CE. The area was known as Judea at that time, and the people are thought to have belonged to a group called the Essenes, a devout Jewish sect.

The majority of the texts on the Dead Sea Scrolls are in Hebrew, with some fragments written in an ancient version of its alphabet thought to have fallen out of use in the fifth century BCE. But there are other languages as well. Some scrolls are in Aramaic, the language spoken by many inhabitants of the region from the sixth century BCE to the siege of Jerusalem in 70 CE. In addition, several texts feature translations of the Hebrew Bible into Greek.

The Dead Sea Scrolls include fragments from every book of the Old Testament of the Bible except for the Book of Esther. The only entire book of the Hebrew Bible preserved among the manuscripts from Qumran is Isaiah; this copy, dated to the first century BCE, is considered the earliest biblical manuscript still in existence. Along with biblical texts, the scrolls include documents about sectarian regulations and religious writings that do not appear in the Old Testament.

The writing on the Dead Sea Scrolls is mostly in black or occasionally red ink, and the scrolls themselves are nearly all made of neither parchment (animal skin) or an early form of paper called ‘papyrus’. The only exception is the scroll numbered 3Q15, which was created out of a combination of copper and tin. Known as the Copper Scroll, this curious document features letters chiselled onto metal – perhaps, as some have theorized, to better withstand the passage of time. One of the most intriguing manuscripts from Qumran, this is a sort of ancient treasure map that lists dozens of gold and silver caches. Using an unconventional vocabulary and odd spelling, it describes 64 underground hiding places that supposedly contain riches buried for safekeeping. None of these hoards have been recovered, possibly because the Romans pillaged Judea during the first century CE. According to various hypotheses, the treasure belonged to local people, or was rescued from the Second Temple before its destruction or never existed to begin with.

Some of the Dead Sea Scrolls have been on interesting journeys. In 1948, a Syrian Orthodox archbishop known as Mar Samuel acquired four of the original seven scrolls from a Jerusalem shoemaker and part-time antiquity dealer, paying less than $100 for them. He then travelled to the United States and unsuccessfully offered them to a number of universities, including Yale. Finally, in 1954, he placed an advertisement in the business newspaper The Wall Street Journal – under the category ‘Miscellaneous Items for Sale’ – that read: ‘Biblical Manuscripts dating back to at least 200 B.C. are for sale. This would be an ideal gift to an educational or religious institution by an individual or group.’ Fortunately, Israeli archaeologist and statesman Yigael Yadin negotiated their purchase and brought the scrolls back to Jerusalem, where they remain to this day.

In 2017, researchers from the University of Haifa restored and deciphered one of the last untranslated scrolls. The university’s Eshbal Ratson and Jonathan Ben-Dov spent one year reassembling the 60 fragments that make up the scroll. Deciphered from a band of coded text on parchment, the find provides insight into the community of people who wrote it and the 364-day calendar they would have used. The scroll names celebrations that indicate shifts in seasons and details two yearly religious events known from another Dead Sea Scroll. Only one more known scroll remains untranslated.

READING PASSAGE 2

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 14-26 which are based on Reading Passage 2 below.

A second attempt at domesticating the tomato

A

It took at least 3,000 years for humans to learn how to domesticate the wild tomato and cultivate it for food. Now two separate teams in Brazil and China have done it all over again in less than three years. And they have done it better in some ways, as the re-domesticated tomatoes are more nutritious than the ones we eat at present.

This approach relies on the revolutionary CRISPR genome editing technique, in which changes are deliberately made to the DNA of a living cell, allowing genetic material to be added, removed or altered. The technique could not only improve existing crops, but could also be used to turn thousands of wild plants into useful and appealing foods. In fact, a third team in the US has already begun to do this with a relative of the tomato called the groundcherry.

This fast-track domestication could help make the world’s food supply healthier and far more resistant to diseases, such as the rust fungus devastating wheat crops.

‘This could transform what we eat,’ says Jorg Kudla at the University of Munster in Germany, a member of the Brazilian team. ‘There are 50,000 edible plants in the world, but 90 percent of our energy comes from just 15 crops.’

‘We can now mimic the known domestication course of major crops like rice, maize, sorghum or others,’ says Caixia Gao of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing. ‘Then we might try to domesticate plants that have never been domesticated.’

B

Wild tomatoes, which are native to the Andes region in South America, produce pea-sized fruits. Over many generations, peoples such as the Aztecs and Incas transformed the plant by selecting and breeding plants with mutations* in their genetic structure, which resulted in desirable traits such as larger fruit.

But every time a single plant with a mutation is taken from a larger population for breeding, much genetic diversity is lost. And sometimes the desirable mutations come with less desirable traits. For instance, the tomato strains grown for supermarkets have lost much of their flavour.

By comparing the genomes of modern plants to those of their wild relatives, biologists have been working out what genetic changes occurred as plants were domesticated. The teams in Brazil and China have now used this knowledge to reintroduce these changes from scratch while maintaining or even enhancing the desirable traits of wild strains.

C

Kudla’s team made six changes altogether. For instance, they tripled the size of fruit by editing a gene called FRUIT WEIGHT, and increased the number of tomatoes per truss by editing another called MULTIFLORA.

While the historical domestication of tomatoes reduced levels of the red pigment lycopene – thought to have potential health benefits – the team in Brazil managed to boost it instead. The wild tomato has twice as much lycopene as cultivated ones; the newly domesticated one has five times as much.

‘They are quite tasty,’ says Kudla. ‘A little bit strong. And very aromatic.’

The team in China re-domesticated several strains of wild tomatoes with desirable traits lost in domesticated tomatoes. In this way they managed to create a strain resistant to a common disease called bacterial spot race, which can devastate yields. They also created another strain that is more salt tolerant – and has higher levels of vitamin C.

D

Meanwhile, Joyce Van Eck at the Boyce Thompson Institute in New York state decided to use the same approach to domesticate the groundcherry or goldenberry (Physalis pruinosa) for the first time. This fruit looks similar to the closely related Cape gooseberry (Physalis peruviana).

Groundcherries are already sold to a limited extent in the US but they are hard to produce because the plant has a sprawling growth habit and the small fruits fall off the branches when ripe. Van Eck’s team has edited the plants to increase fruit size, make their growth more compact and to stop fruits dropping. ‘There’s potential for this to be a commercial crop,’ says Van Eck. But she adds that taking the work further would be expensive because of the need to pay for a licence for the CRISPR technology and get regulatory approval.

E

This approach could boost the use of many obscure plants, says Jonathan Jones of the Sainsbury Lab in the UK. But it will be hard for new foods to grow so popular with farmers and consumers that they become new staple crops, he thinks.

The three teams already have their eye on other plants that could be ‘catapulted into the mainstream’, including foxtail, oat-grass and cowpea. By choosing wild plants that are drought or heat tolerant, says Gao, we could create crops that will thrive even as the planet warms.

But Kudla didn’t want to reveal which species were in his team’s sights, because CRISPR has made the process so easy. ‘Any one with the right skills could go to their lab and do this.’

* mutations: changes in an organism’s genetic structure that can be passed down to later generations

READING PASSAGE 3

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 27-40 which are based on Reading Passage 3 below.

Insight or evolution?

Two scientists consider the origins of discoveries and other innovative behavior

Scientific discovery is popularly believed to result from the sheer genius of such intellectual stars as naturalist Charles Darwin and theoretical physicist Albert Einstein. Our view of such unique contributions to science often disregards the person’s prior experience and the efforts of their lesser-known predecessors. Conventional wisdom also places great weight on insight in promoting breakthrough scientific achievements, as if ideas spontaneously pop into someone’s head – fully formed and functional.

There may be some limited truth to this view. However, we believe that it largely misrepresents the real nature of scientific discovery, as well as that of creativity and innovation in many other realms of human endeavor.

Setting aside such greats as Darwin and Einstein – whose monumental contributions are duly celebrated – we suggest that innovation is more a process of trial and error, where two steps forward may sometimes come with one step back, as well as one or more stops to the right or left. This evolutionary view of human innovation undermines the notion of creative genius and recognizes the cumulative nature of scientific progress.

Consider one unheralded scientist: John Nicholson, a mathematical physicist working in the 1910s who postulated the existence of ‘proto-elements’ in outer space. By combining different numbers of weights of these proto-elements’ atoms, Nicholson could recover the weights of all the elements in the then-known periodic table. These successes are all the more noteworthy given the fact that Nicholson was wrong about the presence of proto-elements: they do not actually exist. Yet, amid his often fanciful theories and wild speculations, Nicholson also proposed a novel theory about the structure of atoms. Niels Bohr, the Nobel prize-winning father of modern atomic theory, jumped off from this interesting idea to conceive his now-famous model of the atom.

What are we to make of this story? One might simply conclude that science is a collective and cumulative enterprise. That may be true, but there may be a deeper insight to be gleaned. We propose that science is constantly evolving, much as species of animals do. In biological systems, organisms may display new characteristics that result from random genetic mutations. In the same way, random, arbitrary or accidental mutations of ideas may help pave the way for advances in science. If mutations prove beneficial, then the animal or the scientific theory will continue to thrive and perhaps reproduce.

Support for this evolutionary view of behavioral innovation comes from many domains. Consider one example of an influential innovation in US horseracing. The so-called ‘acey-deucy’ stirrup placement, in which the rider’s foot in his left stirrup is placed as much as 25 centimeters lower than the right, is believed to confer important speed advantages when turning on oval tracks. It was developed by a relatively unknown jockey named Jackie Westrope. Had Westrope conducted methodical investigations or examined extensive film records in a shrewd plan to outrun his rivals? Had he foreseen the speed advantage that would be conferred by riding acey-deucy? No. He suffered a leg injury, which left him unable to fully bend his left knee. His modification just happened to coincide with enhanced left-hand turning performance. This led to the rapid and widespread adoption of riding acey-deucy by many riders, a racing style which continues in today’s thoroughbred racing.

Plenty of other stories show that fresh advances can arise from error, misadventure, and also pure serendipity – a happy accident. For example, in the early 1970s, two employees of the company 3M each had a problem: Spencer Silver had a product – a glue which was only slightly sticky – and no use for it, while his colleague Art Fry was trying to figure out how to affix temporary bookmarks in his hymn book without damaging its pages. The solution to both these problems was invention of the brilliantly simple yet phenomenally successful Post-It note. Such examples give lie to the claim that ingenious, designing minds are responsible for human creativity and invention. Far more banal and mechanical forces may be at work; forces that are fundamentally connected to the laws of science.

The notions of insight, creativity and genius are often invoked, but they remain vague and of doubtful scientific utility, especially when one considers the diverse and enduring contributions of individuals such as Plato, Leonardo da Vinci, Shakespeare, Beethoven, Galileo, Newton, Kepler, Curie, Pasteur and Edison. These notions merely label rather than explain the evolution of human innovations. We need another approach, and there is a promising candidate.

The Law of Effect was advanced by psychologist Edward Thorndike in 1898, some 40 years after Charles Darwin published his groundbreaking work on biological evolution, On the Origin of Species. This simple law holds that organisms tend to repeat successful behaviors and to refrain from performing unsuccessful ones. Just like Darwin’s Law of Natural Selection, the Law of Effect involves an entirely mechanical process of variation and selection, without any end objective in sight.

Of course, the origin of human innovation demands much further study. In particular, the provenance of the raw material on which the Law of Effect operates is not as clearly known as that of the genetic mutations on which the Law of Natural Selection operates. The generation of novel ideas and behaviors may not be entirely random, but constrained by prior successes and failures – of the current individual (such as Bohr) or of predecessors (such as Nicholson).

The time seems right for abandoning the naïve notion of intelligent design and genius, and for scientifically exploring the true origins of creative behavior.

Time’s up

ANSWERS

1 rock

2 cave

3 clay

4 Essenes

5 Hebrew

6 NOT GIVEN

7 FALSE

8 TRUE

9 TRUE

10 FALSE

11 FALSE

12 TRUE

13 NOT GIVEN

14 C

15 B

16 E

17 A

18 C

19 B

20 D

21 A

22 C

23 A

24 flavour / flavor

25 size

26 salt

27 D

28 A

29 A

30 C

31 A

32 NO

33 NOT GIVEN

34 YES

35 NO

36 NOT GIVEN

37 F

38 D

39 E

40 B

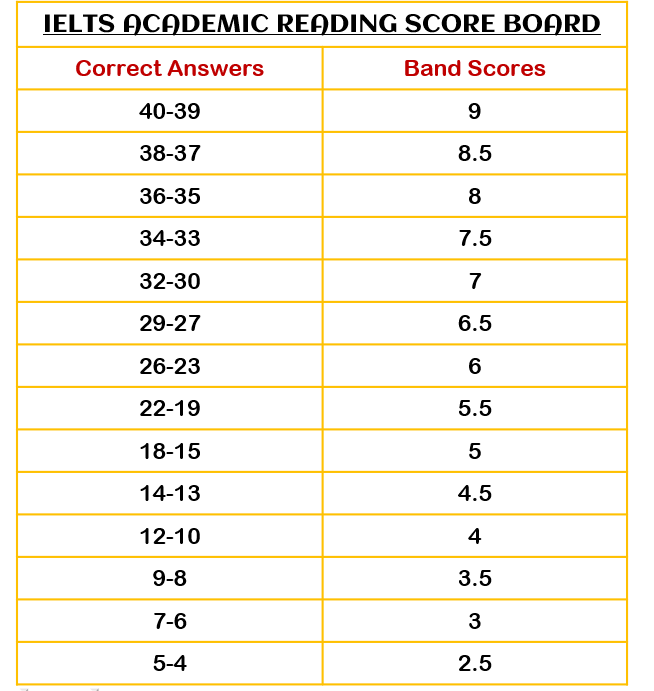

27/40 ( I was practicaly asleep)

31 /40 🙂 7.0

7 (30/40)

36 out of 40…8

34/40

GREAT!