READING PASSAGE 1

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 1-13, which are based on Reading Passage 1 below.

The Industrial Revolution in Britain

The Industrial Revolution began in Britain in the mid-1700s and by the 1830s and 1840s had spread to many other parts of the world, including the United States. In Britain, it was a period when a largely rural, agrarian* society was transformed into an industrialised, urban one. Goods that had once been crafted by hand started to be produced in mass quantities by machines in factories, thanks to the invention of steam power and the introduction of new machines and manufacturing techniques in textiles, iron-making and other industries.

The foundations of the Industrial Revolution date back to the early 1700s, when the English inventor Thomas Newcomen designed the first modern steam engine. Called the ‘atmospheric steam engine’, Newcomen’s invention was originally used to power machines that pumped water out of mines. In the 1760s, the Scottish engineer James Watt started to adapt one of Newcomen’s models, and succeeded in making it far more efficient. Watt later worked with the English manufacturer Matthew Boulton to invent a new steam engine driven by both the forward and backward strokes of the piston, while the gear mechanism it was connected to produced rotary motion. It was a key innovation that would allow steam power to spread across British industries.

The demand for coal, which was a relatively cheap energy source, grew rapidly during the Industrial Revolution, as it was needed to run not only the factories used to produce manufactured goods, but also steam-powered transportation. In the early 1800s, the English engineer Richard Trevithick built a steam-powered locomotive, and by 1830 goods and passengers were being transported between the industrial centres of Manchester and Liverpool. In addition, steam-powered boats and ships were widely used to carry goods along Britain’s canals as well as across the Atlantic.

Britain had produced textiles like wool, linen and cotton, for hundreds of years, but prior to the Industrial Revolution, the British textile business was a true ‘cottage industry’, with the work performed in small workshops or even homes by individual spinners, weavers and dyers. Starting in the mid-1700s, innovations like the spinning jenny and the power loom made weaving cloth and spinning yarn and thread much easier. With these machines, relatively little labour was required to produce cloth, and the new, mechanised textile factories that opened around the country were quickly able to meet customer demand for cloth both at home and abroad.

(* agrarian: relating to the land, especially the use of land for farming)

The British iron industry also underwent major change as it adopted new innovations. Chief among the new techniques was the smelting of iron ore with coke (a material made by heating coal) instead of the traditional charcoal. This method was cheaper and produced metals that were of a higher quality, enabling Britain’s iron and steel production to expand in response to demand created by the Napoleonic Wars (1803-15) and the expansion of the railways from the 1830s.

The latter part of the Industrial Revolution also saw key advances in communication methods, as people increasingly saw the need to communicate efficiently over long distances. In 1837, British inventors William Cooke and Charles Wheatstone patented the first commercial telegraphy system. In the 1830s and 1840s, Samuel Morse and other inventors worked on their own versions in the United States. Cooke and Wheatstone’s system was soon used for railway signalling in the UK. As the speed of the new locomotives increased, it was essential to have a fast and effective means of avoiding collisions.

The impact of the Industrial Revolution on people’s lives was immense. Although many people in Britain had begun moving to the cities from rural areas before the Industrial Revolution, this accelerated dramatically with industrialisation, as the rise of large factories turned smaller towns into major cities in just a few decades. This rapid urbanisation brought significant challenges, as overcrowded cities suffered from pollution and inadequate sanitation.

Although industrialisation increased the country’s economic output overall and improved the standard of living for the middle and upper classes, many poor people continued to struggle. Factory workers had to work long hours in dangerous conditions for extremely low wages. These conditions along with the rapid pace of change fuelled opposition to industrialisation. A group of British workers who became known as ‘Luddites’ were British weavers and textile workers who objected to the increased use of mechanised looms and knitting frames. Many had spent years learning their craft, and they feared that unskilled machine operators were robbing them of their livelihood. A few desperate weavers began breaking into factories and smashing textile machines. They called themselves Luddites after Ned Ludd, a young apprentice who was rumoured to have wrecked a textile machine in 1779.

The first major instances of machine breaking took place in 1811 in the city of Nottingham, and the practice soon spread across the country. Machine-breaking Luddites attacked and burned factories, and in some cases they even exchanged gunfire with company guards and soldiers. The workers wanted employers to stop installing new machinery, but the British government responded to the uprisings by making machine-breaking punishable by death. The unrest finally reached its peak in April 1812, when a few Luddites were shot during an attack on a mill near Huddersfield. In the days that followed, other Luddites were arrested, and dozens were hanged or transported to Australia. By 1813, the Luddite resistance had all but vanished.

READING PASSAGE 2

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 14-26, which are based on Reading Passage 2 below.

Athletes and stress

A It isn’t easy being a professional athlete. Not only are the physical demands greater than most people could handle, athletes also face intense psychological pressure during competition. This is something that British tennis player Emma Raducanu wrote about on social media following her withdrawal from the 2021 Wimbledon tournament. Though the young player had been doing well in the tournament, she began having difficulty regulating her breathing and heart rate during a match, which she later attributed to ‘the accumulation of the excitement and the buzz’.

B For athletes, some level of performance stress is almost unavoidable. But there are many different factors that dictate just how people’s minds and bodies respond to stressful events. Typically, stress is the result of an exchange between two factors: demands and resources. An athlete may feel stressed about an event if they feel the demands on them are greater than they can handle. These demands include the high level of physical and mental effort required to succeed, and also the athlete’s concerns about the difficulty of the event, their chance of succeeding, and any potential dangers such as injury. Resources, on the other hand, are a person’s ability to cope with these demands. These include factors such as the competitor’s degree of confidence, how much they believe they can control the situation’s outcome, and whether they’re looking forward to the event or not.

C Each new demand or change in circumstances affects whether a person responds positively or negatively to stress. Typically, the more resources a person feels they have in handling the situation, the more positive their stress response. This positive stress response is called a challenge state. But should the person feel there are too many demands placed on them, the more likely they are to experience a negative stress response – known as a threat state. Research shows that the challenge states lead to good performance, while threat states lead to poorer performance. So, in Emma Raducanu’s case, a much larger audience, higher expectations and facing a more skillful opponent, may all have led her to feel there were greater demands being placed on her at Wimbledon – but she didn’t have the resources to tackle them. This led to her experiencing a threat response.

D Our challenge and threat responses essentially influence how our body responds to stressful situations, as both affect the production of adrenaline and cortisol also known as ‘stress hormones’. During a challenge state, adrenaline increases the amount of blood pumped from the heart and expands the blood vessels, which allows more energy to be delivered to the muscles and brain. This increase of blood and decrease of pressure in the blood vessels has been consistently related to superior sport performance in everything from cricket batting, to golf putting and football penalty taking. But during a threat state, cortisol inhibits the positive effect of adrenaline, resulting in tighter blood vessels, higher blood pressure, slower psychological responses, and a faster heart rate. In short, a threat state makes people more anxious – they make worse decisions and perform more poorly. In tennis players, cortisol has been associated with more unsuccessful serves and greater anxiety.

E That said, anxiety is also a common experience for athletes when they’re under pressure. Anxiety can increase heart rate and perspiration, cause heart palpitations, muscle tremors and shortness of breath, as well as headaches, nausea, stomach pain, weakness and a desire to escape in more extreme cases. Anxiety can also reduce concentration and self-control and cause overthinking. The intensity with which a person experiences anxiety depends on the demands and resources they have. Anxiety may also manifest itself in the form of excitement or nervousness depending on the stress response. Negative stress responses can be damaging to both physical and mental health – and repeated episodes of anxiety coupled with negative responses can increase risk of heart disease and depression.

F But there are many ways athletes can ensure they respond positively under pressure. Positive stress responses can be promoted through the language that they and others – such as coaches or parents – use. Psychologists can also help athletes change how they see their physiological responses – such as helping them see a higher heart rate as excitement, rather than nerves. Developing psychological skills, such as visualisation, can also help decrease physiological responses to threat. Visualisation may involve the athlete recreating a mental picture of a time when they performed well, or picturing themselves doing well in the future. This can help create a feeling of control over the stressful event. Recreating competitive pressure during training can also help athletes learn how to deal with stress. An example of this might be scoring athletes against their peers to create a sense of competition. This would increase the demands which players experience compared to a normal training session, while still allowing them to practise coping with stress.

READING PASSAGE 3

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 27-40, which are based on Reading Passage 3 below.

An inquilry into the existence of the giffted chilld

Let us start by looking at a modern ‘genius’, Maryam Mirzakhani, who died at the early age of 40 . She was the only woman to win the Fields Medal – the mathematical equivalent of a Nobel prize. It would be easy to assume that someone as special as Mirzakhani must have been one of those ‘gifted’ children, those who have an extraordinary ability in a specific sphere of activity or knowledge. But look closer and a different story emerges. Mirzakhani was born in Tehran, Iran. She went to a highly selective girls’ school but maths wasn’t her interest – reading was. She loved novels and would read anything she could lay her hands on. As for maths, she did rather poorly at it for the first couple of years in her middle school, but became interested when her elder brother told her about what he’d learned. He shared a famous maths problem from a magazine that fascinated her – and she was hooked.

In adult life it is clear that she was curious, excited by what she did and also resolute in the face of setbacks. One of her comments sums it up. ‘Of course, the most rewarding part is the “Aha” moment, the excitement of discovery and enjoyment of understanding something new . . . But most of the time, doing mathematics for me is like being on a long hike with no trail and no end in sight.’ That trail took her to the heights of original research into mathematics.

Is her background unusual? Apparently not. Most Nobel prize winners were unexceptional in childhood. Einstein was slow to talk as a baby. He failed the general part of the entry test to Zurich Polytechnic – though they let him in because of high physics and maths scores. He struggled at work initially, but he kept plugging away and eventually rewrote the laws of Newtonian mechanics with his theory of relativity.

There has been a considerable amount of research on high performance over the last century that suggests it goes way beyond tested intelligence. On top of that, research is clear that brains are flexible, new neural pathways can be created, and IQ isn’t fixed. For example, just because you can read stories with hundreds of pages at the age of five doesn’t mean you will still be ahead of your contemporaries in your teens.

While the jury is out on giftedness being innate and other factors potentially making the difference, what is certain is that the behaviours associated with high levels of performance are replicable and most can be taught – even traits such as curiosity.

According to my colleague Prof Deborah Eyre, with whom I’ve collaborated on the book Great Minds and How to Grow Them, the latest neuroscience and psychological research suggests most individuals can reach levels of performance associated in school with the gifted and talented. However, they must be taught the right attitudes and approaches to their learning and develop the attributes of high performers – curiosity, persistence and hard work, for example – an approach Eyre calls ‘high performance learning’. Critically, they need the right support in developing those approaches at home as well as at school.

Prof Anders Ericsson, an eminent education psychologist at Florida State University, US, is the co-author of Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise. After research going back to 1980 into diverse achievements, from music to memory to sport, he doesn’t think unique and innate talents are at the heart of performance. Deliberate practice, that stretches you every step of the way, and around 10,000 hours of it, is what produces the goods. It’s not a magic number – the highest performers move on to doing a whole lot more, of course. Ericsson’s memory research is particularly interesting because random students, trained in memory techniques for the study, went on to outperform others thought to have innately superior memories – those who you might call gifted.

But it is perhaps the work of Benjamin Bloom, another distinguished American educationist working in the 1980s, that gives the most pause for thought. Bloom’s team looked at a group of extraordinarily high achieving people in disciplines as varied as ballet, swimming, piano, tennis, maths, sculpture and neurology. He found a pattern of parents encouraging and supporting their children, often in areas

they enjoyed themselves. Bloom’s outstanding people had worked very hard and consistently at something they had become hooked on when at a young age, and their parents all emerged as having strong work ethics themselves.

Eyre says we know how high performers learn. From that she has developed a high performing learning approach. She is working on this with a group of schools, both in Britain and abroad. Some spin-off research, which looked in detail at 24 of the 3,000 children being studied who were succeeding despite difficult circumstances, found something remarkable. Half were getting free school meals because of poverty, more than half were living with a single parent, and four in five were living in disadvantaged areas. Interviews uncovered strong evidence of an adult or adults in the child’s life who valued and supported education, either in the immediate or extended family or in the child’s wider community. Children talked about the need to work hard at school, to listen in class and keep trying.

Let us end with Einstein, the epitome of a genius. He clearly had curiosity, character and determination. He struggled against rejection in early life but was undeterred. Did he think he was a genius or even gifted? He once wrote: ‘It’s not that I’m so smart, it’s just that I stay with problems longer. Most people say it is the intellect which makes a great scientist. They are wrong: it is character.’

Time’s up

ANSWERS

1. piston

2. coal

3. workshops

4. labour / labor

5. quality

6. railway(s)

7. sanitation

8. NOT GIVEN

9. FALSE

10. NOT GIVEN

11. TRUE

12. TRUE

13. NOT GIVEN

14. D

15. F

16. A

17. C

18. F

19. injury

20. serves

21. excitement

22. Visualisation / Visualization

23 & 24. B, D (in either order)

25 & 26. A, E (in either order)

27. H

28. A

29. C

30. B

31. J

32. I

33. YES

34. NOT GIVEN

35. YES

36. NOT GIVEN

37. NO

38. C

39. B

40. D

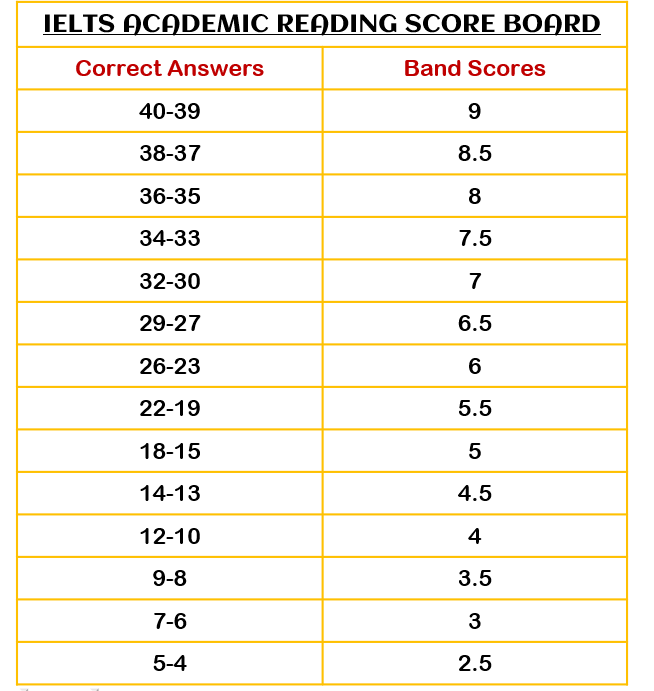

37/40 = 8.5

how to improve this im very frustrated